A Ghanaian manager is leading a virtual meeting with colleagues from Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa. She outlines a new project plan. Her Kenyan teammates nod silently; she takes this as agreement. A South African colleague openly questions the timeline, aiming to strengthen the proposal. Meanwhile, a Nigerian team lead bristles at this challenge, interpreting it as disrespectful. After the meeting, concerns bubble up privately among the Kenyans that never surface in the group. The project slows, and frustration grows.

What went wrong?

Not competence. Not intent. Simply culture.

In Africa’s increasingly cross-border workplaces, the same gestures: silence, nods, challenges, carry very different meanings. Unless leaders know how to decode them, they risk misalignment, mistrust, and stalled progress.

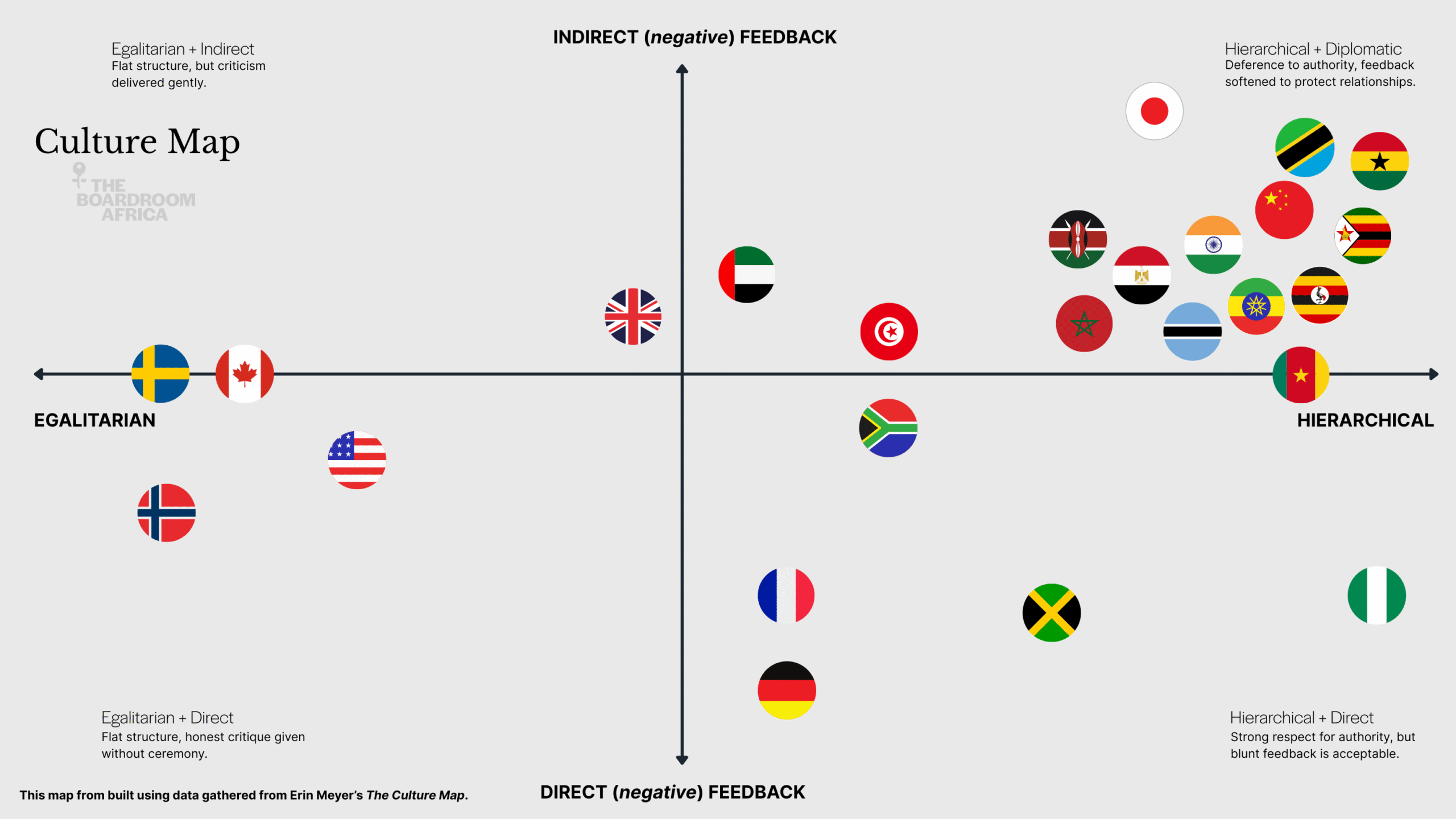

This is where Erin Meyer’s Culture Map offers a powerful lens. Developed to help global leaders navigate cultural complexity, it helps explain why what works in one culture may completely misfire in another.

For instance:

- In France, managers are expected to give feedback bluntly, even if their leadership style is relatively hierarchical. By contrast, in Japan, leaders are highly hierarchical but almost never deliver criticism directly; feedback is softened or communicated indirectly to avoid loss of face.

- In the United States, workplaces look egalitarian on the surface, with a first-name basis, casual dress, open-door policies, but when it comes to decision-making, the boss usually calls the final shot. In Sweden, by contrast, organisations are both egalitarian and consensual: decisions are made slowly and collectively, but once agreed, they rarely change.

- In Germany, employees may openly challenge a leader in the spirit of healthy debate, while in China, that same behaviour could be seen as deeply disrespectful.

These contrasts show why cultural fluency matters: a behaviour that signals confidence in one culture may come across as arrogance or disloyalty in another.

For African leaders, the Culture Map is particularly relevant. The continent encompasses 54 nations, thousands of ethnic groups, and a rapidly integrating business environment. Leaders here are tasked not just with managing diverse teams but with weaving cultural differences into a source of strength.

Why Culture Matters Now in African Leadership

African businesses are scaling faster across borders than ever before. Regional markets are opening. Investors are backing pan-African enterprises. Technology has enabled talent to flow seamlessly between countries, and multinationals run operations that span the continent.

The result? Leaders are rarely managing homogenous teams. They are managing mosaics of culture, where a Nigerian strategist, a Kenyan marketer, a South African finance lead, and an Egyptian operations manager must work seamlessly together. Add to this global partners and diaspora talent returning with external influences, and the leadership challenge becomes more complex still.

The ability to decode and adapt to cultural differences is no longer optional. It is a strategic imperative. Leaders who can navigate these dynamics effectively will unlock trust, cohesion, and performance. Those who cannot risk being misunderstood, sidelined, or left behind.

The Culture Map: A Global Framework

Erin Meyer’s Culture Map breaks cultural differences into eight dimensions that affect how people lead, collaborate, and make decisions:

- Leading – egalitarian ↔ hierarchical

- Deciding – consensual ↔ top-down

- Giving feedback – direct ↔ indirect

- Communicating – low-context ↔ high-context

- Trusting – task-based ↔ relationship-based

- Disagreeing – confrontational ↔ avoids confrontation

- Persuading – principles-first ↔ applications-first

- Scheduling – linear-time ↔ flexible-time

Together, these dimensions form a “map” that helps leaders anticipate where misunderstandings may arise.

Two dimensions are particularly critical in the African context: Leading and Feedback. However, others, like how decisions are made, how trust is built, or how disagreements are handled, also play into the daily reality of cross-border teams.

Leading: Authority and Hierarchy

Across much of Africa, leadership norms lean hierarchical. Respect for elders and authority is woven into social life and spills into the workplace. Deference to seniority is often expected; questioning the boss directly can be seen as disrespectful.

In practice, this means subordinates may hold back from raising problems openly. Leaders are expected to “lead from the front,” to set direction, make final decisions, and maintain formality. Titles, greetings, and symbolic respect matter.

But the picture is not uniform. South African organisations may lean more egalitarian. In Nigeria, hierarchy is more pronounced. Urban multinationals may run flatter than local family firms or public institutions. Even within a single country, generational and industry differences create variation.

The risk arises when expectations collide. A Kenyan consultant educated in the Netherlands may expect open debate, while a Nigerian manager assumes authority should not be challenged. To the Kenyan, silence feels like disengagement; to the Nigerian, questions feel like insubordination. Both misread the other.

Leadership agility is the solution. Great leaders flex. They step into authority when clarity is needed and shift into facilitation when dialogue is called for. Crucially, they signal their approach clearly: “I want everyone’s input on this decision. I’ll take final accountability, but your perspectives matter.”

Feedback: Directness vs. Diplomacy

Feedback norms vary just as much.

- In direct cultures, blunt critique signals honesty and strength.

- In indirect cultures, negative feedback is softened or avoided to preserve harmony.

Across Africa, indirect feedback is common. Saying “yes” may mean “I hear you” rather than “I agree.” Silence might mean respect or discomfort. Colleagues from direct cultures, however, may view this diplomacy as evasive.

This mismatch can cause real damage. A blunt comment may humiliate someone accustomed to diplomacy. A polite silence may leave a leader unaware of problems until it is too late.

The best leaders learn to listen between the lines. They invite private feedback, thank colleagues for candour, and create safe spaces for critique. They also train direct communicators to soften their delivery: “Could we improve this?” lands better than “This is wrong.”

Getting this right doesn’t just avoid conflict; it builds trust. A team that knows how to give and receive feedback across cultures will surface problems early and resolve them constructively.

Other Dimensions in Play

While Leading and Feedback are the most obvious challenges, the other Culture Map dimensions also shape African teams:

- Deciding: Some cultures are consensus-driven; others prefer quick, top-down calls. When these collide, one side sees endless debate, the other sees reckless haste.

- Trusting: In many African settings, trust is relationship-based, built through shared meals, family conversations, and time together. Elsewhere, it is task-based, built through competence and delivery. Effective leaders build both.

- Disagreeing: In some cultures, open confrontation signals engagement. In others, it risks embarrassment and lost respect. Leaders must clarify whether healthy debate is welcome.

- Scheduling: Flexible-time cultures may treat deadlines as guidelines; linear-time cultures see them as commitments. Misalignment here can derail projects.

Each dimension reminds us that Africa is not one culture. It is a mosaic of influences, indigenous traditions, colonial legacies, and global exposure that shape how work gets done.

Common Pain Points for Cross-Border Leaders

- The “yes” that doesn’t mean yes. Agreement may be politeness, not commitment. Silence may mask doubt.

- Decision whiplash. In hierarchical settings, bosses decide quickly, but may revisit later. In consensual settings, decisions are slow but final. Misalignment frustrates both sides.

- Perceived insubordination. What feels like healthy debate in one culture feels like disrespect in another.

- Trust gaps. Relationship-oriented leaders may find task-focused colleagues “cold,” while the latter see the former as “inefficient.”

- Time clashes. Flexible vs. rigid approaches to deadlines can create tension if expectations are not aligned.

These are not signs of poor leadership. They are signs of cultural misalignment, and they can be addressed.

Practical Guidance for Leaders

- Adapt your style. Flex between authority and facilitation. Learn what your team expects, and signal your approach.

- Decode carefully. Probe when you hear “yes.” Invite private feedback. Train yourself to hear what is unsaid.

- Blend trust-building. Invest in relationships and deliver consistently. Both matter.

- Set explicit norms. Agree as a team on how to make decisions, give feedback, and handle disagreement. Don’t leave it to guesswork.

- Model curiosity. Ask questions, show humility, and celebrate diverse styles. When leaders respect differences, teams follow.

A Visual Culture Map for Africa

Download the Map

The Leadership Dividend

Cultural fluency is not a soft skill. It is a strategic advantage.

Leaders who can read the map and adapt unlock alignment, trust, and creativity. They turn potential culture clashes into collaborative energy. They build teams that not only coexist but thrive on difference.

In Africa, this skill is even more powerful. Our diversity is our edge. Leaders who master cultural agility will build stronger organisations, scale more effectively, and model a kind of inclusive leadership the world sorely needs.

Closing Call to Action

The future of leadership belongs to those who embrace culture as a compass, not an obstacle.

Learn to read between the lines. Learn to flex between authority and dialogue. Learn to value both results and relationships.

Do this, and you will not just manage cross-border teams, you will transform them into cohesive forces that are greater than the sum of their parts.